HOLLYWOOD SEX SCANDALS GO WAY BACK

Decades ago, Warner Bros. studio mesmerized moviegoers with films such as "The Jazz Singer" and "Casablanca" — some of the most popular hits of cinema's golden age.

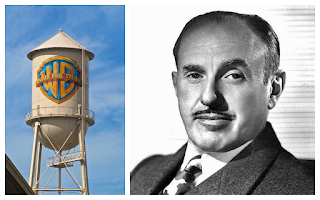

Now, the four Jewish-American brothers who founded that studio — Jack, Harry, Sam and Albert — are the marquee attractions of a new book: "Warner Bros: The Making of An American Movie Studio," by film critic and historian David Thomson.

It's part of Yale University Press' Jewish Lives series, and the protagonist is studio head Jack Warner — a walking paradigm of Hollywood success and scandal.

Warner is "maybe the biggest scumbag ever to get into a Jewish Lives series," writes Thomson. But when Yale suggested Thomson take up the Warner Bros. for the series, the acclaimed author of 20 books was intrigued. It hadn't occurred to him to write about a corporation, he told The Times of Israel.

He said, "certain corporations that were absolutely vital in the history o movies were largely or almost entirely Jewish. … I was always very interested in the way in which Jewish culture had so much to do with the foundation of movies."

"The most important factor of all is that I really felt, for me personally, Warner Bros. was the great studio," he said.

The family's original name was either Wonsal or Wonskolasor. Of the four brothers, the older three — Harry, Albert and Sam — "were all born in what was either Poland or Russia depending on the frontiers at the time," Thomson said.

In the late 19th century, their father, Benjamin, immigrated to the US and changed his last name to Warner. His sons Moses, Aaron and Shmuel became, respectively, Harry, Albert and Sam.

Harry Warner, left, and Sam Warner, of Warner Bros. Studios. (Public domain)

"I think, back in Europe, they had a hard time," Thomson said. "They were not nearly as poor as some, but they were not well-off. Because they were Jewish, I think they were subjects of a great deal of hostility."

As the family moved across North America, they lived in Canada, where in 1892, a baby boy named Jacob wa born; he would become Jack.

They relocated to Youngstown, Ohio, trying their hands at various career paths including operating a bowling alley.

One night in 1903 or 1904, Sam Warner suggested something different: As his brothers sampled their mother Pearl's potato latkes with applesauce and sour cream, he used a recent technological phenomenon — a movie projector — to show a 1903 film, "The Great Train Robbery," on a sheet pinned to the wall.

"If Sam had not really urged it upon them, they might have done something else altogether," Thomson reflected.

Follow the celluloid road

Moviemaking in that era was a path well-traveled by Jewish Americans, according to Jan-Christopher Horak, director of the UCLA Film & Television Archive and a professor of critical and media studies.

"Almost all of them were immigrants from the shtetl, Jewish, from Russia or Eastern Europe," Horak said. "Louis B. Mayer, Fox, Samuel Goldwyn, whose real name was Goldfish."

"[At] the beginning of the 20th century in this country, there was still a lot of anti-Semitism," Horak explained. "Certain professions, they were maybe not legally banned from, but it was extremely difficult to get into. At the beginning of the 20th century, what you had was the creation of, the invention of, motion pictures. A lot of Jewish immigrants saw this as a way to get into something in which there was no competition."

However, they faced anti-Semitism from first-generation film producers such as Thomas Edison, Horak said. "In the period to 1912, there were a lot of anti-Semitic statements that 'these Jewish pushcart peddlers are taking over the film business, destroying the morals of our youth, etc., etc.' — from the right wing, of course," he said.

But circa 1915-1917, Jews moved into production "and pretty much invented Hollywood," he said — referencing film critic Neal Gabler's 1988 book "An Empire Of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood."

"He was the first to write about it," Horak said. "Up to that time, it had been a taboo subject — that someone thinking about it would say that it would be anti-Semitic. In 1912, it happened that most of the producers themselves … did not make films with Jewish themes. [They wanted to] appear completely American. So much of America, in the heartland especially, was anti-Semitic. They di not emphasize the fact they were Jewish."

But one Jewish-themed Warner Bros. film — "The Jazz Singer," released in 1927 and marking its 90th anniversary this year — left a lasting imprint on technology when it pioneered the use of sound. It was Sam Warner who "had a demonstration of sound on film and thought there was great promise," Thomson said.

"'The Jazz Singer' really made silent films untenable," Horak said. "That film was so popular that it really changed the genre. MGM, Paramount, even the big studios had resisted sound. The technology was there, they had seen it work, but they were not willing to put in the investment.

Warner Bros., previously a relatively minor studio, was put on the map by the film and set on its way to becoming one of the major studios, he said.

"The Jazz Singer" is "far and away the most Jewish film they ever made," Thomson said. "The way in which the hero is torn between being like his father, a cantor, and being a show business star."

Jolson — a cantor's son himself — played Jackie Rabinowitz, who changed his name to Jack Robin. (Jolson controversially performed in blackface, which Thomson writes is "an archetype that is offensive today.")

Al Jolson in 'The Jazz Singer.'

Feeling guilty over abandoning family and faith, Robin returns to his dying father and sings Kol Nidre on Yom Kippur before resuming his show-business career.

Tragically, Sam Warner "died virtually the same moment 'The Jazz Singer' opened," Thomson said. "Others said he died from the intensity, the work, the strain of getting sound. I think he had other health problems."

A rift developed among the surviving brothers. "[The film] dramatized the story between Harry and Jack," Thomson said. "Harry was like a respectable old-style Jew. Jack was never interested in that. He wanted a quite different life."

Jack, the proto-Weinstein

Thomson called Jack "a womanizer" who "liked to tell jokes and sing … a show-off, a showman."

"Harry and Jack fell into a pretty emotional competition," Thomson said. "In time, Jack dominated his brothers."

The studio prospered nevertheless, with gangster films like "Little Caesar," and social commentaries such as "I am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang."

Thomson noted Bette Davis' impact on "a very male studio."

"In the late 1930s, she was a hugely important star, maybe one of the most important female stars Hollywood ever had," he said. "For a period, in the late 1930s, early 1940s she was nominated for an Oscar five times in six years."

Later, Warner Bros. found roles for another female screen legend: Joan Crawford.

"I think they liked women who were suited to tough guys," Thomson said. "They did not like milquetoast characters. They believed in making people with bold, vigorous, independent, tough attitudes."

This would be true for the legendary Warner Bros. cartoon characters as well — Thomson said his favorite character, Bugs Bunny, has a cockiness and arrogance similar to James Cagney and Edward G. Robinson.

And toughness would be crucial in motivating World War II audiences. Warner Bros. rose to the challenge particularly with "Casablanca," released in 1942 and still powerful 7 years later. Thomson calls it "the ideal American picture."

"Casablanca" tells the story of Rick (Humphrey Bogart), an American nightclub owner in Vichy French Morocco — "a loner, cynical, looking out for himself," Thomson said.

Rick is torn between convincing his former lover, Ilse (Ingrid Bergman), to stay with him or helping her escape the Nazis with her Czech resistance leader husband, Laszlo. Ultimately, in the Academy Award-winning adapted screenplay, he tells Ilse she must leave with Laszlo or regret it — "Maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow, but soon and for the rest of your life."

"'Casablanca,' in 1942, was at the height of the anti-Nazi film wave," said Horak. "In 1942, American studios made 60 to 70 films with anti-Nazi themes."

That contrasted with prewar years. "Until 1939 or 1940 in Hollywood, there was no single negative film [about the Nazis]," Horak said. "The Jewish producers themselves did not want to highlight the fact."

While the 1937 Warner Bros. film "The Life of Emile Zola" addressed the Dreyfus Affair and became the studio's first Best Picture Oscar winner, Thomson writes that Jack Warner deleted any line referring to Dreyfus as a Jew, at the insistence of Georg Gyssling, the German consul i Los Angeles.

Earlier, in 1934, a Warners representative in Berlin was brutally beaten by Nazis; Jack Warner falsely wrote that he was murdered and that this compelled him to close the studio's Berlin office (the Nazis closed it down themselves). For a time, Warner Bros. continued doing business with Germany.

But Warner Bros. was also "the first [studio] to pull out of Germany, no longer distributing films," Horak said, while MGM and Paramount "continued to distribute to Germany as late as 1939, 1940, removing names of Jewish staff and filmmakers so they could be distributed."

Thomson said that "more than most other studios," Warner Bros. was "alerted to, and alarmed at, anti-Semitic elements [in] Europe in the 1930s. Like most people, they believed [the war] had to be fought and won, it was a just war, a necessary war."

But Horak knew of only two wartime films that directly addressed the Holocaust: "The Mortal Storm," by MGM in 1940; and "None Shall Escape," by Columbia in 1944.

Horak said that "people in the know, people who follow certain films, know that virtually all the secondary roles, especially all the refugee roles, are German-Jewish actors, with accents, and so, they're visually very present."

"Once the war was over, Americans would buy their own houses in the suburbs, and everybody got a TV," Horak said.

Amid this changing atmosphere, in the 1950s, Jack Warner convinced Harry and Albert that they would all sell off their shares in the studio — but Jack double-crossed them and bought back the company.

"Many in the family felt that the way Jack behaved hastened Harry's death," Thomson said.

Jack Warner himself died in 1978. He left a legacy of professional achievement and personal scandal, divorcing his first wife, having a daughter with the woman who became his second wife, and alienating his son Jack Jr.

His era is associated with unsavory images of power-hungry studio head and the casting couch — which have reappeared with Weinstein.

"The womanizing habits coming out that Harvey was prone to have a long history in the film business," Thomson said. "Attitudes change. We're shocked now."

"Once upon a time," he said, "the general feeling was that women going into the movies to get a job as an actress … should not be surprised if they were propositioned, if they had to do pretty nasty things to get ahead. It happened across the whole film business. It's regrettable."

Horak said that "Louis B. Mayer was known as an unbelievable satyr, the Harvey Weinstein of back then. Harvey Weinstein was doing it at a time when you couldn't do it any more. You had the women's movement in the late 1960s, early 1970s.

"That kind of sexual harassment just is no longer socially acceptable. It was only because he was so powerful that he continued to do that. He's probably not even the only one. It certainly needs to be condemned. He's getting his just deserts now," he said.

Warner Bros. itself became corporate behemoth Time-Warner, and briefly AOL Time Warner. The "WB" logo remains on current blockbusters, including "Wonder Woman."

But, Thomson said, "The world has changed so much. Studios used to be fun affairs. A bunch of people who worked together. Now, they're corporations, part of an industrial enterprise. I don't think there's anything of the original impulse."

Comments

Post a Comment